Nova Lisboa – Délio Jasse

6 Sep, 2018 - 4 Nov, 2018

In my travels around Angola, I often met people who refused to be photographed, saying they would not allow their souls to be stolen by the camera’s lens. Perhaps because they did not know what the pictures would be used for, or because of the intrinsic aloofness of the photographer, in certain cultures a photograph is never just a means of freezing an instant; it also has an esoteric dimension.

The chance of a camera being an efficient extractor of souls has not yet been scientifically proven. However, we are aware of its ability to resuscitate memories buried by the perpetual passing of time.

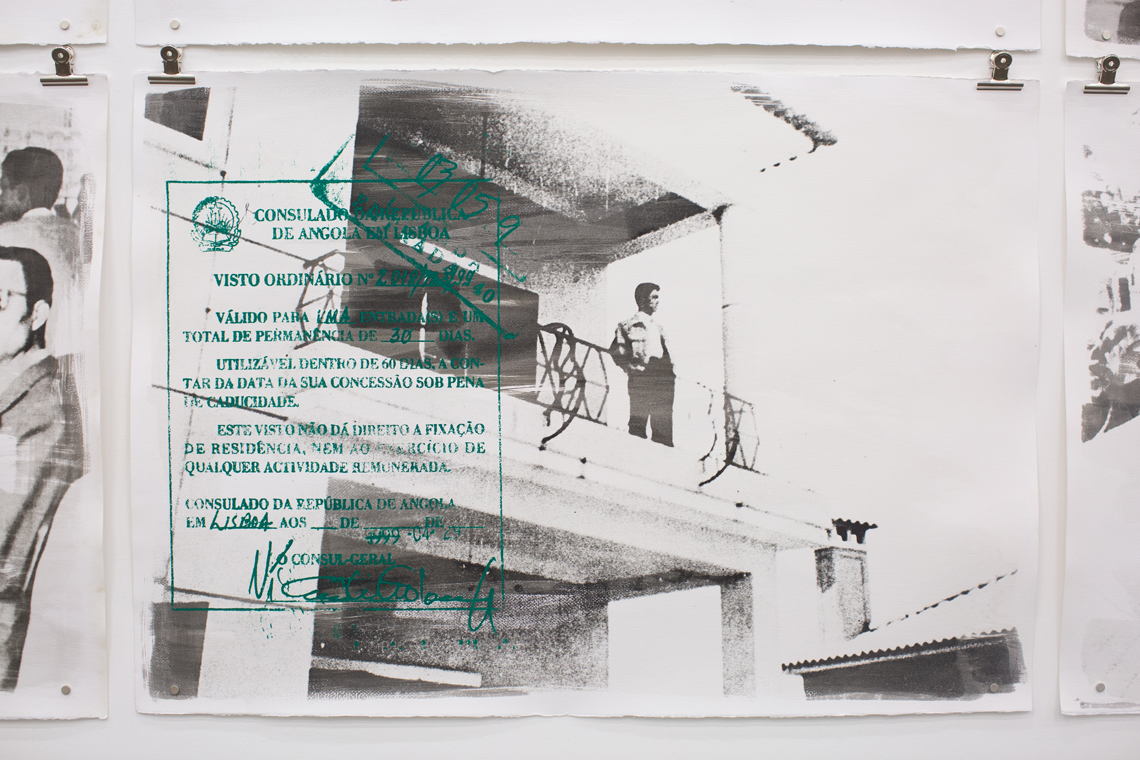

The work artist Délio Jasse has produced around photography and documents inherited from the colonial era reanimates images once consigned to a dead archive, scattered around markets or, simply, thrown in the garbage. By presenting this work in the public realm, Jasse has given these artefacts of memory a second life. In his creative process, he photographs the original images printed on paper, transferring them back onto the negative, to give them a new support, a new dimension. The light of the magnifier reawakens the ghosts of another age while the image submerges into the cotton paper, which is converted into the host body for the souls stolen over half a century ago.

The photographs Jasse works on and which make up the largest part of the “Nova Lisboa” (New Lisbon) exhibition were bought at the flea market in Lisbon. The portraits were taken in Huambo, a city baptised in 1928 – during the colonial regime – as Nova Lisboa, which became the main stronghold of colonial expansion on Angola’s central plateau. Nova Lisboa is a further example of a city whose origins lie in an ambitious dream to turn Angola into a Portuguese overseas “province” (and not just a colony) that became reality. The solidity and grandeur of the houses and buildings in the city, like many cities in Portugal’s former African empire, demonstrate a clear intention to consolidate a colonial presence on which the sun would never set.

In these photographs we can see a period in history that shaped our contemporary life profoundly and permanently, and which we feel very reluctant to address. While they represent an era in which photography was the exclusive preserve of the dominant class, a gift few had access to, in Jasse’s creative process these portraits are an important legacy, one that transcends the purely appealing aesthetics to allow us to assemble the shards of the hostile history of a country where successive traumatic episodes caused an irreversible erasure of memory.

In Jasse’s work, one of the predominant aspects is the relationship between photography and memory. The artist appropriates an outsider’s gaze, manipulating it aesthetically without fully altering its visual narrative, but drawing our eyes into a trap where we are obliged to ask complex and at times disturbing questions.

When we observe the people in these portraits, we are confronted by the reminiscence of a process of colonisation that built a society founded on racial segregation, contradicting the Luso-tropicalist fantasy of the good settler. The graphics taken from documents and superimposed on the images with garish colours using silkscreen printing take us back to the concept and aesthetics of Pop Art, a paradox since the graphics are taken from documents which would have turned a segregated society into a day-to-day reality. Taking these portraits as a starting point, what segregation does is to create contradictory sentiments between the delectable nostalgia of a privileged minority and the disavowal of a brutally exploited majority. All of history can be interpreted in multiple ways, like a work of art, and in Jasse’s work the myriad readings available to the observer are left open in an approach that is utterly unpretentious.

The magic in Jasse’s work occurs above all while the magnifier’s light in his studio remains turned on, at the moment when the images gradually come to the surface of the paper. Once the artwork has been created, it may or may not go back to being an archive, but never a dead one. The urgent questioning of the observer will never return peace to these souls which, once again, have been stolen. Each of us can contextualise from our own personal and intimate perspective, but we cannot deny its contribution to the collective memory and understand the mimicking of colonialism in today’s society, even in the deplorable behaviour of those currently in power. There are those who prefer to live submerged in the revivalism of colonial and post-colonial discourses, but social phenomena today have become too complex to dismiss the subsidy of history, a vital subsidy that can only be achieved once we shed our fears and prejudices.

Kiluanji Kia Henda, 2018